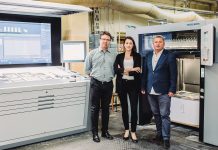

A conversation with Krzysztof Kubiak – the author of Children of a Lesser Gotham, the novel published in May 2021 in English, in New York, currently prepared for Polish edition – nominated for the title Leader by Vocation. He built houses to then write a book about the big-city homeless – people often gifted and having dreams – who used to wine and dine from porcelain and are now forced to beg for handouts. The novel’s also about transformation of the protagonist, a wealthy man who, just in time, recognises existential problems of the poor, trying to change their fate. Despite the seriousness of the matter, the book is written in a cheerful way, with a positive message. The author is also going to tell us about the path he took before making a decision to try his hand at the literary genre of a novel.

What made you outstanding in teenage years?

From my early school years I was passionate about photography and still am today. When I was 8 years old, my uncle gave me a widescreen resolution camera, which quickly made me fall in love with photography, and by the age of 11 I already had my own darkroom, in a room adapted for this purpose and equipped with the necessary accessories, with a large wardrobe where you could take the film out of the camera without risking exposure and place it in the correx for developing.

My dream was to become a cameraman in the future and, as we all know, childhood dreams often change and I was later seduced by poetry, literature and sport. Perhaps it was meant to be this way, because nothing happens by accident, there’s always a reason and necessity. I rarely parted with my camera. I often took it with me on longer or shorter hikes, or on family or sporting trips, and I must mention here that I trained football from the age of 10, later playing in the provincial junior league. Taking photos and then developing them gave me great pleasure. It was even a kind of adventure and a reason to get out of the house.

As I lived two kilometres from Żelazowa Wola – Fryderyk Chopin’s birthplace – in spring and summer, when the park and the manor house were bustling with life and piano music was playing in the neighbourhood, I would take my camera and set off. It was a great experience for me to get a closer look at people from all over the world, and let me remind you here that this was the early 1970s. Simultaneously, I absorbed music, which, since then has practically become my best companion. I still nurture my love for Chopin, but also Mozart, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and many others, whom I often listen to relax and improve my mood. Occasionally, I have also managed to photograph some famous faces, such as Cardinal Wyszynski in 1974.

From earlier events, I remember 1969, when the Apollo 11 crew landed on the moon, and I photographed the black-and-white television screen with blazing eyes, documenting this epoch-making event. I might add that this trip to the moon also ignited my love for astronomy and space science, or as we would say today, astronautics. I used to persistently search for books on the subject and it was not an easy task at the time. And so I managed to buy the first one in a bookshop near my home. It was a book entitled “Building rockets and rocket engines”.

Additionally, I was also fascinated by chemistry. One day in 1974, I found a book ‘Chemical Wonders and Oddities’, which someone evidently discarded and from then on I wanted to have a small laboratory at home. My mother and my chemistry teacher at primary school helped me to modestly assemble the accessories. Used and chipped flasks, menzies, burners, etc. that were destined to be thrown away were sometimes given to me as gifts. But reagents were really difficult to get. Some of them could be bought at the chemist’s, others, such as acids, I bought from car repair shops. My first chemical experiments were simple. I grew crystals, coated small metal objects with copper or observed various chemical reactions.

The moment I was ready to go deeper into chemistry, a small incident happened and…ended my home experiments. I inadvertently knocked over a flask filled with hydrochloric acid put on the table. The acid trickled down the glass top of the table onto the recently purchased woollen carpet, considerably damaging its texture. It’s easy to guess what it looked like, but my parents forgave me.

At the age of sixteen, maybe seventeen, I started writing poetry. My first poetic attempts were not very successful. On the surface, the world was beautiful and perfect, and that was the mood of the poems, but when juxtaposed with the reality around me, it was a bit naive and overdone. Then, for my own satisfaction, I tried writing some song lyrics. I had, and I think I still have the ease of creating coherent rhymes filled with meaning. However, I must admit that without melody it is not the piece of take. My six-year older brother made me fall in love with rock music. He was a musician – a drum player. He introduced me to the music community, through which I met many interesting people.

My first vocal attempts were really promising. In the nineties, I composed a song on guitar and wrote lyrics to it. Then, in the Warsaw located recording studio owned by the Kram group leader, Ryszard Pokorski, who created the arrangement, I sang the song and delivered it to the Radio dla Ciebie radio station. It didn’t break through in the charts, so I thought the musical path wasn’t for me.

I then decided to focus on sport, which I regret a little today, because sport is not always synonymous with health. A rather unpleasant and painful cruciate ligament injury was followed by a break from football. When my knee healed, I decided to attend kickboxing classes at the Warsaw University of Technology, but after a few months my knee gave out again. I was still full of energy, but when my daughter was born, I gave up sports. Temporarily. In New York, when I had already forgotten about the old injury, I enrolled in the Krav Maga section at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan. As the saying goes: three times lucky. After a year of training, I noticed that my knee was not completely stable, while Krav Maga requires 100 per cent fitness. This period’s also abundant in good and pleasant memories. I met a lot of colleagues there – great people, also instructors previously serving in armies in the Middle East, who taught me how to be mentally strong, sensitive to harm, and at the same time how to defend myself in case of danger, and that sometimes you have to give way to avoid unnecessary trouble.

You’ve had a lot of passions. How did your career path unfold?

My brother attended mechanical engineering college and so did I, following in his footsteps. I wasn’t too happy about it because deep down I felt I was a humanist. I read a lot of literature and poetry. I was fascinated by Herbert, Poświatowska, Grochowiak, Stachura, Czechowicz, Apollinaire, and sometimes even wrote poems myself to subsequently send them to literary competitions. I applied to the Academy of Physical Education, but I was not accepted, and the army soon claimed me. I was sent to the Naval Specialist Training Centre in Ustka, and after a six-month course of study I was sent to Gdańsk. The entire service lasted two years. I was saved from the full three-year service, which is how long it takes on vessels, by the fact that my home communication unit was located on land in Gdańsk near the Naval Hospital. From that difficult service, I gained knowledge of the Morse alphabet and I think that’s how I really became a grown-up and mature man. On night duty I had a lot of time to read, think, and there was a fairly well-stocked library in the building, the keys to which were held by a colleague of mine. Many books were also sent to me by my mother. At that time I became acquainted with the works of Kafka, Bulgakov, Nabokov, Mann, Proust, Vonnegut or Gombrowicz, Boy-Żeleński, Iwaszkiewicz and several others. The last two names translated literature at the masterpiece level. The first three are my favourite writers, but every other author brings something new to our spiritual development. My deep interest went also towards philosophy, especially thinkers whose writing style I really enjoyed. I started reading the works of Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Arthur Schopenhauer, Bertrand Russel and several others. I took my first serious job at a housing cooperative founded in 1989 by some friends of mine. At the age of 28, I was entrusted with a management position when I had not yet mastered the ins and outs of construction. I was taught by an experienced site manager, who was unable to personally oversee the entire project full-time due to his multiple jobs. It was a difficult time for me because I was responsible for practically everything. I was responsible for both the materials in the warehouses and the construction site. Thrown in at the deep end, I had to deal with dozens of older employees, professionals who had their own grooves and habits, but after a while we got to like and respect each other. In three year-time we completed the building, which housed 64 flats and shop units. Thanks to this work, I managed to get my own 70-square-metre flat. Of course, I had to repay the loan and, in addition, work off a social contribution of around 2,500 hours in the form of holidays or simply hire someone to do auxiliary work. Luckily, my father worked some of these hours for me, which I am endlessly grateful for. After leaving the cooperative, my brother and I ran a trading company for several years. We opened a grocery shop and then an electrical goods shop. However, my brother moved into the music business and I found that trading was not my cup of tea. Still, I have a lot of respect for traders and their hard work. I know how tough the business is.

How come you went to the US?

My father had two uncles in the U.S., pre-war emigrants from the 1920s. I was curious about the fate of the family and in 1979 I received an invitation. However, I didn’t manage to go then, because of my young age and general problems concerning going west. I did not get a passport. It wasn’t until 2002 that the opportunity arose. Before that, I had started to learn the basics of English at home from my ESKK lessons. That year, in May I flew to New York. The beginnings weren’t easy. But I took comfort in the fact that I wasn’t the first to face the hardships of emigration. Artists, teachers, athletes, all rolled up their sleeves and worked hard. To supplement my English education, I enrolled at Kingsborough Community College on the ESL programme. I settled nearby in the Russian-speaking, oceanfront neighbourhood of Brighton Beach, where Janusz Głowacki used to live and write about the place. I very much enjoyed his memories of ‘Little Odessa’. My places of living changed with my jobs, which made a perfect way of saving time for a good night’s sleep instead of wasting it on travelling.

In New York you also worked for a construction company?

Yes, I obtained the necessary licences and authorisations and history from Poland repeated itself in the U.S. Again I was thrown in at the deep end. And again I was responsible for all the work performed – compliance with the art of construction, punctuality, professionalism – and these were jobs at great heights, dangerous and requiring a lot of manual skills and ingenuity. I worked with Poles, Americans, Indians, Irish, Pakistanis. I learned about their culture, cuisine and customs. Sometimes they invited me to their homes.

What did you do in your spare time?

I travelled and explored the country. I got acquainted with 26 North American states, Mexico and the Caribbean, with a camera at hand, of course. I know New York better than I know Warsaw, I walked around the whole city, divided each neighbourhood into squares and on weekends and days off I walked around and photographed. My collection includes, among others, several hundred photos of New York murals. When I felt the need to put my thoughts on paper, I wrote. In 2005, I started writing my first novel, Woman of War. It is a lifestory of a woman I met in New York. I didn’t finish it. At some point I felt it was too sad a story. A story of a girl abused in her family home. A period of growing up in a neighbourhood where it was better not to venture out in the evenings. Then a teenage crush on an inappropriate boy, and the first experience with soft drugs, culminating in a two-year stay in a female prison on Rikers Island in the East River. As you might guess, what followed was a real life school, a struggle for survival and dignity. Everything ended happily, but for me it was too difficult to write. Maybe one day I will finish this story.

Then you wrote a touching story – a tribute to New York’s homeless. How long was Children of a Lesser Gotham written?

I started it in 2016, but I had already entertained the idea of writing something about the homeless, because I had met so many wonderful people who were once artists, musicians, soldiers, and ended up on the streets, but also people who no one would shed a tear for. I show New York, a city of great wealth and extreme poverty, and still present mechanisms of indifference and loneliness. However, I am not describing the martyrdom of homelessness, I am writing – in a rather cheerful tone – about the fact that they have their world on the street and feel comfortable there at times, although it is hard to tell. Maybe it’s a matter of some kind of freedom or just habit and a lack of faith in improvement. The main character is a wealthy banker who experiences sudden appearance of a mysterious figure out of this world at night. Tormented by remorse, in the morning he goes to confession, a very long confession. The eccentric bishop listens to him, or rather conducts a verbal clash, and finally sets him a penance: to serve the poor and share his wealth with them, which the rich man does not accept with enthusiasm.

Magical realism?

A multi-layered plot combining magical realism with harsh reality. There is a lot of metaphysics, poetic descriptions, but also dialogues; the first 40-page chapter is all dialogue. It’s a multidimensional, eclectic novel combining different literary genres: drama, detective story, thriller, science fiction.

It’s kind of a paradox, you built houses to then write about the homeless.

A man is a Nomad. He doesn’t always attach himself to places. Everything in the novel is fictitious, there are no themes of mine, just thoughts.

Did you write in English?

No, in Polish, the novel was translated into English. I met an American journalist of Polish origin and he translated the text. The final editing was done by another American journalist from the well-known The Nation Magazine and New York Focus magazines. It was published in paperback by Penumbra Bookery. It is also available in an electronic version, on Amazon.

What are your plans?

I decided to take advantage of early retirement and am now applying for it. I will be 62 in September. I want to pursue my passions.

What are you most proud of?

Of my daughter. She’s 35 and lives near Warsaw. She is a linguist with a degree in English. I am also proud of my good relations with my closer and more distant family and friends, and of the fact that I have had the opportunity to get to know many cultures, nations and regional cuisines.

What are your dreams?

I would like my novel to be published in Poland and people to enjoy reading it. I would also like to persevere in my resolve to write song lyrics. It would be good to have someone shout them out through microphone one day.

Dorota Kolano

Beata Sekuła