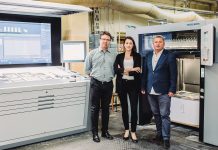

Is it true that Bartosz Węglarczyk became a journalist by accident? He tells our readers what true journalism and effective management is all about. He emphasises mutual respect and listening to other people, among other things. This recognised foreign correspondent and editor-in-chief of the onet.pl portal was awarded the title Leader of vocation in the category Leader in the media and media management for his outstanding achievements in both those areas.

This story begins in a specific place, in Czerniaków – a part of Mokotów, which at that time did not have the best reputation in Warsaw. Bartosz Węglarczyk is an only son and lives only with his mother, which has a huge impact on his life and shaping of his personality. He has to quickly learn how to take care of himself. He is also the youngest boy in the yard and still has to fight for his own. He wears glasses, so he is in a weaker position from the beginning. ‘My childhood memories are connected with numerous fights,’ he says with a smile. ‘I make a distinction of this period as before or after a particular fight. It gave me the strength to speak openly about what I think.’ Learning in primary school is a difficult time for him. He starts it a year earlier. He is in a class where many people flunk it for two or three years in a row. He becomes its president.

The period of high school is much easier for him. In order to have money for his expenses, he started working at an early age. ‘The most lucrative activity for me was collecting dry bread,’ he recalls. ‘People would come by cars and buy it for animals. This gave me real financial independence for the first time.’

After graduation, he starts working in the media, which, he claims, is a complete coincidence. The year is 1989. He goes out for a walk with his dog, passes his school, which is located near his home, but the pet does not turn right as usual, but goes left instead. Bartosz sees two men fixing up a plate with the inscription “Solidarność” (Solidarity), which is a great surprise for him. He offers them help because he sees that they have a problem with the wall falling apart. The gentlemen suggest that he should visit the editorial office, where the lady employed there asks him what he can do. He replies ‘nothing’, and she says that in that case, he can make coffee and tea for journalists. When he returns home, his mum teaches him how to brew these drinks in large quantities. This is how Bartosz Węglarczyk starts working in Gazeta Wyborcza.

His main task is to remove viruses from computers using a floppy disk. He presses the right keys and the editors look at him like he is a wizard. While working in a newspaper, he completes his studies in journalism at the University of Warsaw. He writes his first article a year later. It’s about… increases in the fees for using public toilets in Warsaw. ‘The most important thing for me at that time was to get to know people from whom I could learn a lot,’ he says. ‘I owe them a lot. I remember an article about labour camps in China, which took me three days to write. Young journalists often think that after a month’s work they will have their text published in the newspaper. However, it is actually something if they manage to publish a note. I’ve learned from my own mistakes. My mentors used to say, ‘Bartek, you only have to change a small thing here.’ And almost the entire text had to be rewritten. It is good to meet such people in your life.’

Soon, Bartosz Węglarczyk receives an offer to work in the foreign department of Gazeta Wyborcza. Other journalists are amused when he says that he wants to become a correspondent in America. ‘I believe that if you want something, you have to take it or say it out loud,’ he emphasises. This principle translates into his further professional success.

From being a correspondent for Gazeta Wyborcza to working for Onet

He becomes a correspondent in Moscow, even though at the end of high school he tells his teacher that he will never say a word in Russian again. It is 1996, a week after returning to Poland he meets his teacher of Russian. When she asks him how he was communicating in Russia, they both burst into laugh.

He earns 400 dollars there, which is a huge amount of money. From that period he remembers, first of all, poverty – it is a difficult period for Russians; a time of great sadness. He goes to places afflicted with armed conflict. He reports on them, and after years of collecting all these events, he writes a book about Russian rocket armies. The Russian army is his great passion. ‘Russians are fascinating, they are a very wise nation,’ he adds. ‘It’s a pleasure to discuss political or philosophical issues with them. At the time, I did not appreciate this nation and I did not like to be there. I left Moscow in 1996 and returned in 2007 and it was a totally different world, completely unrecognisable.’

After returning from Russia, he goes to Brussels for a year. ‘A lot was going on then, we started negotiations with NATO and we were entering the EU,’ he recalls. ‘I came there straight from Moscow and it was a real cultural shock for me. Everything was new and extremely fascinating.’

In 1996 he receives a scholarship from The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists at the University of Chicago. He begins to write a book about military operations in Russia and also about the Pentagon, but the U.S. Department of Defense buys rights to the book and keeps it secret. ‘I was not the first one to whom this procedure was used,’ he says.

After 9 years of working for Gazeta Wyborcza, he finally fulfils his great dream and goes to Washington for 6 years. He is a correspondent from 1998 to 2004. There, he meets Kinga Rusin, with whom he will host a morning TVN programme in the future. ‘I became a true Americanophile back them,’ he reveals. ‘I felt good in the States and if I couldn’t live in Poland, that’s where I would live. America is a country of diversity and vast spaces. I like practically everything there: the desert in Texas, thousands of kilometres of highways, Los Angeles, Hawaii – everything is beautiful. But I love America the most for not having to turn the steering wheel for a thousand kilometres.’

When he returns, he becomes the head of foreign department of Gazeta Wyborcza, where he continues to work until 2011. ‘After 22 years, I decided that it was necessary to try something else,’ he admits. ‘You can’t spend your entire life in one place.’ He becomes the editor-in-chief of Sukces (Success) magazine. He works there for a year in a three-person team, brews coffee again, but also performs many other duties. Publishing a monthly in such a small team and with such a small budget is extremely difficult. However, he gets to meet interesting business people, such as Wiesław Włodarski, the President of FoodCare, who created one of the largest companies in Poland and started with sweeping the floor in an ice cream parlour.

In 2013–2016, Bartosz Węglarczyk becomes the deputy editor-in-chief in the daily Rzeczpospolita (Republic), and also runs the morning show Dzień dobry TVN (Good Morning TVN) on the weekends with Kinga Rusin or Świat magazine in TVN 24 BIS. In March 2016, he becomes the programme director of Onet.pl, and since December 2018, he takes over the duties of the editor-in-chief, also being responsible for the direction and program line of the portal.

Contemporary journalism

‘Listening to and getting to know people is the essence of journalism,’ he explains. ‘Empathy was needed in TVN. When I was asked to run Dzień dobry TVN (Good Morning TVN), it made me laugh at the beginning, but I almost immediately agreed. However, the articles need to be structured as if you are sitting in a pub with friends and telling them the story that has happened to you today. I admit that writing is a difficult art that we learn all our lives.’

He and his colleagues created a text about the Noble Gift, and it took them six months to finish it. They edited it 200 times. The day before the publication, they improved a few more details. Bartosz Węglarczyk believes that there is no such thing as an ideal article, you can always add or change something in it. However, as he stresses, it is important to show the readers which information is the most important.

‘Journalism is a profession in which we have to provide information and interpret why something is happening and what are the consequences,’ he explains. ‘I can say, for example, that the Prime Minister will increase taxes. But I can also explain that these taxes will be higher and society will have less money. These are two different things. In sports journalism, the commentator explains why Poland lost a match against Portugal. The result of the match is one thing, but saying that Poland played in a certain way and explaining this event is another.’

The editor-in-chief of Onet notes that in recent years, editorial staff in general was reduced by half. When new technologies such as the Internet appeared on the market, interruption of the market occurred, which changed almost all business models of journalism. Many things fall apart because we are unable to make profit, and the public believes that journalists can work for free. The trips themselves are very expensive. Sending someone to the war in Syria to stay there for a month and move about safely costs about 20–30 thousand dollars. Polish editorial staff often rely on journalists who go there at their own expense.

‘I remember when I was with Tomek Wróblewski (former editor-in-chief of Newsweek Polska and Wprost, among others) in the United States,’ he states. ‘We wanted to enter Haiti during the internal unrest, when the president Aristide was overthrown. We waited at the border until they let us in. As Polish journalists we had no money for bribes. And the American crew was equipped with everything they needed. They had satellite phones, new equipment and enough money to move around and bribe. The Polish crew was so poor that it did not even have bulletproof vests or phones. When we got lost in the jungle, we got stuck there for 3 days. This information reached the media with a few days’ delay.

Bartosz Węglarczyk says that journalism can be frustrating nowadays. Once in a while, he checks what the public writes about him on the Internet. Sometimes it helps to improve oneself. Many people believe that the measure of success is, unfortunately, the number of enemies. The more enemies you have, the more you have accomplished in your life.

He sees fake news as a manipulation of facts and it has nothing to do with journalism, but the problem is in education. The system does not teach us how to discuss and dispute. We yell at each other, lie to each other, but we do not discuss. ‘For me it’s terrifying that we don’t learn that lesson at school and we see it from different perspectives,’ says Bartosz. ‘At school, I learned everything by heart. There were situations where I disagreed with the teachers and left the classroom. In American schools, it is customary for children to bring some kind of object from home once a week, e.g. a pebble or a teddy bear. Children are supposed to tell why they have chosen that particular thing. At first, I didn’t understand it; only after some time, I realised that it was a form of learning self-presentation. The children asked each other about the subject which led to a discussion.’

Leader with respect

‘I believe that my entire team deserves the Leader of vocation award, which was awarded to me by the Programme officials,’ Bartosz Węglarczyk emphasises. ‘A well-functioning team, which I manage and of which I am proud, is a hallmark of a well-chosen leader.’ He also notes that there are different types and features of managers. Some are very modest, but some are arrogant and cocky. Donald Trump is an example of a leader who lacks modesty altogether, but undoubtedly feels like a true-born leader.

‘I think there are different leaders, even those who practice fear-based management,’ he says. ‘Whether they are good leaders or not, that’s another matter. You can observe this in sport. There are trainers who are bossy, almost like dictators. Many people believe that this is acceptable in this field, and even positive if it produces the expected results.’ The editor-in-chief of Onet cannot imagine that he could work that way. He says, however, that this method can be effective in some places, e.g. in the army. American general George Patton’s management, for example, was based on terror. His subordinates were terribly afraid of him, but on the other hand, he was one of the most effective commanders of the World War II.

Curiosity about the world is what he values in a journalist. ‘I know people who claim that they know everything, and there are also those whose pupils dilate when they talk about what they would like to see,’ he says. ‘I appreciate young people who have a thousand ideas per minute, but that’s what the bosses are for – to guide them.’ He often discusses with them and then makes decisions that they should understand. Even rookie journalists have the right to vote here. Leaders must also know how to listen. ‘A negative aspect of being a leader is one-man decision making,’ he notes. ‘This must be done taking into account everyone’s interest – the company, employees and mainly the public.

The greatest pleasure for Bartosz Węglarczyk are the successes of Onet journalists, which happen quite often lately. Onet is part of a large media group with many corporate standards, the same as in Belgium, Germany and Czech Republic. ‘I devote a lot of attention to mutual respect,’ he stresses. ‘That is a very important thing. In our company, this principle is respected starting from the boss all the way to the very first step of the career ladder. Young people often think that authorities are unnecessary. Of course, this cannot be imposed – either you are an authority for someone or not. If someone tries to impose their authority, that person will not become respected.’ The society itself chooses authorities based on their achievements. It’s their independent decision, which consists of many factors.

‘I believe that managing journalists is extremely difficult,’ Bartosz Węglarczyk admits. ‘Arrogance is our occupational disease. We must work on this and watch out on this trait. Being an editor is one thing and managing people in media industry is another matter.’ He says that they are independent; they do not work like workers on the assembly line. Quite the contrary; they often rebel! They have a well-earned opinion on every subject and they stick to their opinion.

Other passions and love

Bartosz Węglarczyk loves animals and is actively involved in helping them. He financially supports shelters and various charity events. He used to have a dog; now, there are two stray cats living with him, but he loves all animals.

His next love are films of every genre. At home, he has a collection of five thousand films. In addition, he is still interested in the military. ‘I know that this is a specific passion,’ he says with enthusiasm. ‘If someone spends all the time on it and digs deep enough, it is possible to verify every detail. Now, I am most interested in the political decision-making process concerning Special Forces. Acquiring knowledge on this subject requires regular commitment.’

His fascination with America continues. During his holidays, he loves to travel around the United States by car. He has already done it ten times. He usually travels 17 thousand kilometres every two years, visiting 11 states in three weeks! It is the best kind of recreation for him. Perhaps he will go there again this year. In the end, journalists fulfil themselves on the road.

Beata Sekuła