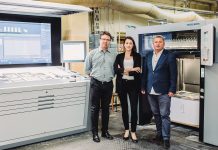

An interview with dr Artur Szklener – musicologist, academic teacher, director of the Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Warsaw, who listens to every musical genre. Dr Artur Szklener has just been awarded the title of Leader by vocation.

Are you a born leader or a formed one?

I do not particularly feel like a leader. I specialise in the music by Fryderyk Chopin, our greatest composer, and for this reason I work at the Fryderyk Chopin Institute. We have a wonderful ensemble and I feel honoured leading it – in that sense it is sort of leadership, but understood more as working together for the Chopin heritage. Both, my colleagues and I are convinced that Chopin’s music is not only congenial works, but also an amazing opportunity to show us, Poles, and people worldwide that Polish culture, Polish classical music, is a work of extraordinary value that we should not forget. This is the main purpose of our Institute: to cultivate the heritage and knowledge of Fryderyk Chopin and his work, but also to educate and encourage young people to actively participate in it. Professor Jerzy Żurawlew, the initiator of the International Chopin Piano Competition, claimed that the main aim of the competition was to encourage young people to take an interest in music in the same way they’re into sports. Such an approach we find the finest.

When did you discover music?

Already in the cradle. My father is an amateur musician and a music lover. As far as I remember, from an early age classical music sounded in the family home. I don’t know the world without it. At the age of five or six, I started learning to play the piano, then went to primary and secondary music school. My sister plays the violin and graduated from the Academy of Music in Krakow, so my parents’ house was filled with the sounds of instruments. After high school graduation, I studied musicology at the Jagiellonian University, where I also defended my doctorate. The dissertation, ‘Idiomatic Chopin’s melodics’, dealt with a certain system, a musical language, which, I’m convinced, Chopin created and used consistently. It’s a fully universal language, because Chopin referred to the tradition of his great predecessors. In his works, we can hear echoes of the music of Bach, with his melody pliability and dynamism of harmony, of Mozart, a classicist committed to the ideals of beauty and proportion, and of Beethoven, a romantic classic who brought many emotions to music, from which Chopin did not escape, but rather explored them in his works, and finally of the virtuosos of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was a time when music was moving from aristocratic theatres in palaces to public concert halls. Audiences and tastes were changing. There was a great explosion of fondness for the piano – an instrument accessible to the bourgeoisie on the one hand, and developing so rapidly that in time it could replace the orchestra on the other. Such a cultural environment was an excellent background for the development of Chopin’s talent. He was educated in Warsaw and became acquainted with Polish, German, Italian and French music. It is reported that in addition to his constant presence in the capital’s rich music life, he would sit for hours at Brzezina’s Music Store (today we would say: in a music bookshop) and study (music) scores. So when leaving Poland, he was a well-educated, knowledgeable pianist and compositional genius capable of creating his own language.

What’s your favourite piece of music?

There isn’t one. Musical output is so abundant… As time goes by, tastes change. I often listen to Baroque or Classical Period music, but I don’t run away from contemporary pieces. When I was younger, I co-organised festivals, both of early and recent music by Krakow composers. Music is divided into good and bad, and I’m convinced you can find very good music even in genres on the verge of music, such as rap or hip hop. I often listen to jazz, sometimes rock or popular music. I’m therefore a ‘music omnivore’.

How did your professional path evolve?

My professional artery divides into two vessels: one related to the university (from 1997 to 2011 I taught at the Institute of Musicology at the Jagiellonian University) and the other to the Institute. I have been working at the Institute since its formation in 2001. In 2009, I became deputy director for science and publishing, and in 2012, I won the competition for a director.

How many employees does the Institute have?

Approximately, 130 staff members and several times more associates. We are a specific cultural institution, because we’re defined by the scope regarding a particular artist, rather than the type of activity specific to theatres or philharmonics. We combine the functions of a museum – we have two branches: in Warsaw and Żelazowa Wola; we’re an organiser of music life – we organise the Chopin Competition, the ‘Chopin and his Europe’ festival, and numerous concert series; we’re a phonographic publishing house – we’ve published almost 200 titles with music not only by Chopin; we are a book publisher and also an entity supporting scientific research.

Is there a concert hall within the facilities of the Institute?

Yes, a small one, for 70 people, in the Fryderyk Chopin Museum in Warsaw. We also organise concerts in Żelazowa Wola, the Chopin’s birthplace. One of our missions is to support young artists, and every week the museum hosts concerts by completely unknown young pianists. They’re recorded and then assessed by an expert committee to be recommended support appropriate to the abilities and needs of the musician in question. We provide the best ones with a kind of patronage: we enable them to attend concerts organised by our partners at home and abroad. We also invite them to masterclasses, and sometimes we even manage to acquire instruments to make them available to those musicians.

Where do you get funds from?

Our organiser is the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. We also attempt to raise funds from private sponsors and patrons. We generate income from ticket sales, both to the museum’s branches and to the several hundreds of events we organise each year.

You are also involved in educational activities….

One of the important objectives of the Institute is to carry out educational activities in the broadest possible sense. My personal contribution in this respect has been primarily concerned with popularisation of knowledge and access to Chopin’s music through new media. When I took over as head of the Institute, electronic media were developing rapidly, and we became pioneers in building an audience beyond the concert hall and beyond the country’s borders. For many years, we’ve been building an international community of music lovers, not only of Chopin, and we count the number of our subscribers on social media in the hundreds of thousands. This is possible thanks to Chopin’s popularity worldwide and conscious, systematic decades-long efforts.

Please, name the achievements you’re most proud of.

First and foremost, of the reach we have managed to build around the Chopin Competition. Independent agencies have calculated that information about the event reached as far back as 2015. 5 billion people around the world, and the competition was followed by almost 30% of Poles. During the pandemic period, we had around 40 million competition broadcast views. These are numbers comparable to mass events and unattainable in the world of so-called high culture. We can be proud, as this proves the worldwide phenomenon of the Polish artist.

What do you plan for yourself as a Director and for the Institute?

We’d like to focus on the Fryderyk Chopin Museum to make it even more visitor-friendly. Our major objective is also the construction of the International Music Centre in Żelazowa Wola, where we plan to create a concert hall, plus educational, workshop and conference spaces. This will enable incorporation of the musical experience into regular visits to Chopin’s Birthplace and carry out regular educational activities aimed at young musicians. We’re also preparing to celebrate the centenary of the Chopin Competition in 2027.

How do you relax?

My greatest pleasure is exploring Mediterranean culture. My wife and I take advantage of every moment we can get away from reality and visit more and more corners of southern Europe. I occasionally happen to sit at the piano, but much more often I just listen to good music.

Dorota Kolano

Beata Sekuła