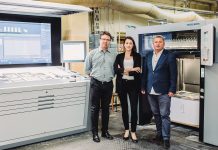

An interview with Prof. Krzysztof Morawski, MD, PhD, a renowned otolaryngologist, head and neck surgeon, audiologist, and phoniatrist in Poland and internationally. In 2000, he received a Fulbright scholarship. He is an outstanding physician, but also a scientist and educator. He promotes hearing aids and implants that improve the quality of life. He has just been awarded the title of Leader by Vocation.

Do you consider yourself a leader?

I never aspired to be a leader. For me, it stemmed from natural situations that arose naturally in school and college. Back then, people gathered around me, and I simply did my job, worked, took responsibility, and didn’t let up. I think it’s a matter of character and the role model I learned at home – my mother was extremely hardworking. I inherited this hard work from her. I don’t create artificial hierarchies; I don’t need “followers.” I prefer authority built through competence, reliability, and consistency.

Sports and music have been a part of your story from the beginning. What did they shape in you?

I’ve loved sports since childhood. I practiced track and field. In college, I won the Medical University’s high jump championship. It teaches humility, consistency, and the ability to endure defeat. Music was also a part of my life—I attended music school. Music, in turn, develops sensitivity, ear for music, and discipline. These two worlds complement each other greatly. Today, I see how sports and music have influenced my work style: precision, rhythm, consistency—and simultaneously curiosity and openness.

You’re from Częstochowa and studied in Łódź. What were your early career like?

I graduated from high school in Częstochowa, then studied medicine in Łódź. My first job was at the provincial hospital in Piotrków Trybunalski—the hometown of my wife, an ophthalmologist. This stage gave me a solid clinical foundation. When I moved to Silesia, a serious adventure with science and specialization began. It was a time of intense work and learning about responsibility for decisions, the team, and the patient.

Professor Mariola Śliwińska-Kowalska, a renowned otolaryngologist, appeared along the way. What did you learn from this master-disciple relationship?

A lot. The professor once told me a sentence that became my principle: “Don’t bang your head against a wall. You have to go around the wall.” I also repeat this to young people: “If something doesn’t work, go around the obstacle, look for an alternative, wait. You lose time and motivation when you hit a wall.” This way of thinking changed my approach to my career and education. Instead of being frustrated by difficulties, I sought new paths. When complications arose with continuing my specialization, I completed my doctorate and moved in a direction where I could truly discover and contribute something.

You devoted your doctorate to audiology and the study of musicians – including absolute pitch. Why this choice?

In the 1990s, new techniques were emerging – including objective studies of the cochlear’s receptor response. I collaborated on this with Professor Rakowski from Warsaw, whose articles were cited worldwide, especially in Japan. Thanks to him, I had access to advanced, objective tests. We tested 50 musicians. The results were fascinating: some people convinced they had absolute pitch didn’t show it in the tests; others – on the contrary – had a predisposition, though they didn’t claim it. This is an important lesson: a “good ear” is an innate ability to recognize pitch and repeat it. The musical sense also encompasses timbre, harmony, and the relationships between frequencies – talent must then be consistently cultivated. This research resulted in a publication, which I am still referred to.

After your doctorate – Zabrze and the Silesian Medical University under Professor Namysłowski. What did this stage teach you?

It was a time of strong clinical and team training. Eleven years of work in Silesia solidified my skills and prepared me for the next step – a scholarship in the US. In Zabrze, I learned how to combine clinical work, teaching, and research so that one reinforced the other.

The year 2000 brought you a Fulbright scholarship to Miami. How big a difference was that?

A huge one – technologically and organizationally, there was a huge gulf between us. I spent 13 months at the Otolaryngology Clinic at the University of Miami. I worked in intraoperative audiology, including animal models – a “leapfrog” towards modern methods of real-time hearing assessment. Later, I returned for three-month grants until 2005. We co-developed research with teams from the US and Poland, resulting in publications, patents, and new solutions. This experience opened many doors for me, but above all, it broadened my horizons.

After returning – Warsaw, your habilitation and professorship. Why the capital?

Warsaw offered greater opportunities: the clinic on Banacha Street with Professor Niemczyk, access to projects, international collaboration, and facilities for implementing new technologies. In 2009, I completed my habilitation, and in 2015, my professorial appointment was signed.

Today, you head the Otolaryngology Clinic at the University Clinical Hospital in Opole. What have you built there?

Since 2021, we have been developing a modern clinic in Opole with a pediatric ward and a full cochlear implant program, which I co-founded. We have patients of all ages – from infants to seniors. In a child with congenital deafness, implantation is possible as early as around six months of age. It’s amazing how quickly the brain learns to respond to auditory stimuli if intervention is made early and diagnostics and rehabilitation are well planned. On the other hand, we don’t hesitate to operate on people in their 70s and 80s, because it significantly improves quality of life, stimulates activity, reduces isolation, and supports cognitive function.

What does modern hearing implant technology look like?

Today’s implants are high-end devices. Computer-programmed, monitored via phone, with extensive memory settings, and designed to work with artificial intelligence. The average lifespan of the system is approximately 20 years, with proper use and monitoring. However, the key is the entire process—proper qualification, extensive diagnostics, perfectly planned surgery, and, equally important, auditory rehabilitation after implantation.

You also have a strong social mission—to “demystify” hearing aids and implants. Where did the idea for this fashion show come from?

I would like hearing aids to be treated as naturally as glasses. I dream of a fashion show where children and adults with hearing aids or sound processors walk the runway proudly. It would send a beautiful message: “I hear better, I live more fully—this is my strength, not something to be ashamed of.” Such a gesture breaks barriers, changes the narrative, and can help you take the first step toward help.

How to care for your hearing—from fetal life to late adulthood?

We start with the mother. Avoiding noise, adopting a healthy lifestyle. After birth, newborn hearing screening is performed, and if the results raise doubts, a full objective diagnosis, preferably while the child is asleep. Then, daily care: limiting and treating infections appropriately, avoiding exposure to smoke, and caution with ototoxic medications. Noise is the biggest enemy for young people. Loud discos, headphones on full blast, and chronic stimulation. For adults and seniors, it’s crucial not to delay fitting hearing aids if hearing loss develops. They must be of good quality, because the brain needs sound stimulation. And if hearing aids aren’t sufficient, an assessment of eligibility for an implant is necessary. Today’s health awareness is growing, and that’s encouraging, because hearing isn’t an “add-on”—it’s about the quality of relationships, work, and safety.

What kind of leader are you to your team and young doctors?

One who listens carefully first and only then sets expectations—for themselves and others. In medicine, the goal isn’t a race, but continuous development of competence and responsible decisions. I teach students and residents to think flexibly: if a given path isn’t working, we analyze the causes, change the plan, and look for a more effective solution. Maturity means acting wisely, not stubbornly; what matters is the outcome for the patient, the team, and the science.

How do you recharge your batteries?

I value peace, quiet, and long walks – by the sea and in the mountains. My wife and I often escape to the Baltic Sea. I also enjoy meeting friends, but moments of solitude are equally important to me. I have two sons. The older one is an laryngologist. It’s a great joy when children choose the path they know from home, but on their own terms.

What are your plans?

We’re expanding the clinic in Opole; I teach, conduct workshops, and travel extensively across Poland. The media and journalists are doing a tremendous job here, because thanks to them, more and more people are learning that effective solutions to hearing problems exist: hearing aids, implants, and rehabilitation. I would like even more patients to hear, literally and figuratively, “you don’t have to live in silence.” This is my personal mission.

Katarzyna Raszka