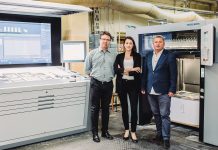

Prof. dr hab. Krzesimir Dębski is one of Poland’s most outstanding musicians and composers of our time. Although he considers classical music to be his domain, he is also known for composing film, television, and jazz music. In 2000, he won the Fryderyk Award for Composer of the Year and the Philip Award for the Ogniem i mieczem soundtrack. A year later, during the Olympia International Film Festival in Pyrgos, Greece, he was awarded for W pustyni I w puszczy score.

In 2017, he was rewarded with Pro Patria Medal for outstanding contribution to preserving the memory of the struggle for Poland’s independence and for activity supporting commemoration of the Volhynia massacre victims. The medal is a personal matter for the artist – his family comes from Volhynia, and his parents survived the tragic events of 1943. Prof. Dębski actively participates in cultural and educational initiatives to preserve the memory of those events, merging an artistic message with historical mission.

His numerous awards include: the ZAiKS 100th Anniversary Prize (2018), the SAWP Award for 50 years of artistic work (2022), the Award of the Marshal of Wielkopolska for lifetime achievement (2023), the Artistic Award of the City of Poznań (2023), the Gloria Artis Gold Medal for Merit to Culture (2024), and the Grand Prix Jazz Melomani award for lifetime achievement (2024).

As an outstanding conductor and professor, he guides young artists on their musical paths and popularises music in all its forms and sounds. The artist has just been awarded Leader by vocation.

Your biography reads that you have composed over 70 symphonic works, four piano concertos, three violin concertos, music for over 100 films and TV series, for theatre performances and Teatr Telewizji, as well as an opera. It doesn’t even take a thorough analysis to notice that many of these compositions were created at the same time. And yet, your creative work is only a part of your activities, because there are also concerts, performances, rehearsals, including those with the String Connection band you lead, as well as philharmonic concerts and festivals. You’ve also written a book entitled Wołyń. Nic nie jest w porządku. Are your days somewhat longer?

I wish they were. One would always like to have more time, but proper organisation allows me to accomplish everything I’ve planned. Pre-empting your question, I must say I don’t consider myself a workaholic, but rather a person who can effectively use each moment. This is definitely an advantage, but simultaneously a disadvantage, because I’m busy all day long, and work probably takes up 80 percent of my time.

However, I’m not complaining, because I’m one of the lucky few who really love what they do.

Did you always know that you would be a musician and composer? When did this fascination begin?

Certainly not in childhood years. My father headed a music school, so I naturally ended up there too. Organisation was his incredibly strong point. After the war, our family of Volhynia origin, experienced forced displacement and were thrown to Wałbrzych. Even in those difficult times, my father graduated from the Poznań conservatory and began to organise a music school. He created another one in Kielce, and then another in Lublin. Back then, in order to study music, you had to finish regular elementary school and high school separately. It meant a lot of work for every musical student. In regular school, I preferred to sit somewhere at the back, and so did I in music school. I would be lying if I said I worked hard. At that time, I didn’t feel the same flow for music as I did later. Even the teachers had told my father that since I didn’t have a drive for music, it might be better not to push me, but my mother insisted until I myself felt this could be my destiny and passion for life.

Was it a process, or was it decided by some special event?

It was more of a process than a sudden epiphany, although the latter would probably sound better. In those days, music schools weren’t exclusively for children. Mine, for example, was also attended by musicians from the military orchestra, and even by their bandmaster. After all, they had to find a way and place to learn music. I was able to easily help them because of already being able to write down any melody I heard. This made me think that if I, such a young child, could already teach adults, then maybe I should devote myself to music. So I made it to middle school, where I really felt it to be my world.

However, you didn’t solely focus on classical music, but reached for various genres.

I’m still attracted to them, although with age I’m more of focused on classical music, where I feel most comfortable and which I consider to be my true domain, even though I’m probably associated more with lighter pieces regarding cinema, theatre, or television, including popular TV series, even though not everyone pays attention to who wrote the music – oftentimes the hallmark of a film.

Such as Dumka na dwa serca for Ogniem i mieczem…

Indeed. Generally speaking, I believe that every film should have its own theme. Contemporary directors sometimes disagree with me on this, which I consider a mistake. I happen to joke that by such disagreement they’re not only giving up a hallmark, but also considerable royalties for subsequent theme performances.

Ogniem i mieczem was particularly important, wasn’t it? And not only because of the music you wrote for it?

Yes, it was. That’s understandable. My family comes from the Eastern Borderlands. My grandfather, who was a doctor, and my grandmother, a teacher, were murdered there in 1943, and I searched for traces of them wherever possible for years. The war profoundly affected my family, so it’s obvious that my sentiment for the areas we were expelled from is deeply rooted in me, even though it’s no longer connected with personal memories.

Let’s get back to the beginning of our conversation for a moment. Having such a busy schedule, do you find time to rest? And if so, how do you regain strength for new challenges?

I don’t need to rest because I don’t work. As the saying goes, those who devote time to their passion don’t work. But seriously, I’m not fond of literally understood vacations and rarely let myself get persuaded to take one. I get bored quite quickly and start looking for something to kill time. There’s even a funny story related to this. When it was already known that I would be composing music for the aforementioned Ogniem i mieczem, my family managed to persuade me to go to Spain. Indeed, the beach and the water were attractive, but only for a moment, so I found a piece of paper and wrote Dumka na dwa serca on the Spanish sand. Many of my compositions were created while in the car, on the plane, the train and other unusual circumstances. I definitely prefer short breaks. The day after a concert, on my way back I see a lake. I stop, go for a swim, and then continue driving. That’s enough for me and I don’t even know why I would spend a week there.

So, do real leaders ever rest?

I have no idea. I don’t think of myself that way at all. Besides, it wouldn’t make sense. The people I work with would have to see me the leader way, not me myself. Yes, I conduct large orchestras, the musicians listen to my comments and conclusions, but I just do my job the best I can. I simply try to make everything play in tune.

Piotr Góralczyk